- Home Page

- Accepted

Paintings & Copies - Doubtful

Attributions - Doubtful Textual References

- Alternative

Titles - Collectors &

Museums - Bibliography

- Search Abecedario

- Watteau &

His Circle

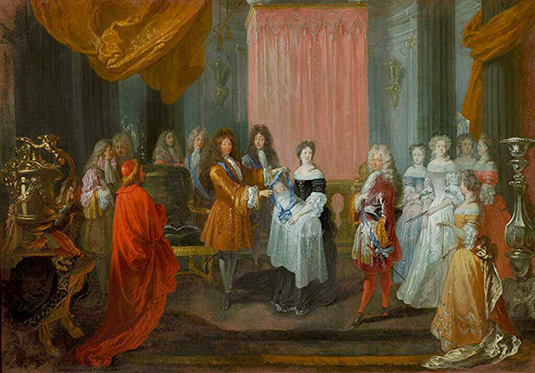

Louis XIIII metant le cordon bleu à Monsieur de Bourgogne

Entered May 2025

Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawi, inv. M.Ob.1310 MNW

Oil on canvas

64 × 91 cm

ALTERNATIVE TITLES

Louis XIIII mettant le cordon bleu à Monsieur de Bourgogne

Louis XIV awards the Cordon Bleu Order to the Duke of Burgundy, father of Louis XV

Louis XIV remettant le cordon bleu au duc de Bourgogne

Louis XIV donnant le cordon bleu à Mgr le duc de Bourgogne au berceau

Louis XIV revêtant du Colier de l’Ordre le jeune Dauphin

Die Ludwig der Vierzehnte dem Herzog von Bourgogne nach der Taufe den heiligen Geistorden umhängt

Ludwik XIV dekoruje orderem cordon bleu księcia Burgundii, ojca przyszłego Ludwika XV

Louis XIV. in der Kindheit mit vielen Personaggen

Louis XIV revêtant du Colier de l’Ordre le jeune Dauphin

Ludwig der Vierzehnte dem Herzog von Bourgogne nach der Taufe den heiligen Geistorden

Luigi XIV impone il “Cordon Bleu”al duca di Bourgogne

La Naissance du duc de Bourgogne

RELATED PRINTS

In 1729, Nicolas de Larmessin engraved Watteau’s painting, Louis XIIII metant le cordon bleu a Monsieur de Bourgogne,in the same direction. The print was announced for sale in the September 1729 issue of the Mercure de France (p. 2244).

PROVENANCE

Paris, collection of Jean de Jullienne (1686-1766; director of a tapestry factory). Julienne’s ownership of the painting is cited in the engraving’s caption: “Tiré du Cabinet de Mr de Jullienne.” The picture is not listed in the illustrated catalogue of Jullienne’s collection, c. 1756, now in the Morgan Library and Museum, New York.

Potsdam, collection of August Wilhelm von Preussen (1722-1758) in 1758. By descent to his brother Friedrich Heinrich Ludwig von Preussen (1726-1802). His inventory, 1760, fol. 2r : “1. Stück Louis XIV. in der Kindheit mit vielen Personaggen und vergoldeten Rahm.”

Probably in the collection of Earl Stefan von Kwilecki (1839-1900, member of the German Parliament); by descent to Elzbieta Eliza Kwilecki.

Purchased in 1965 from Elzbieta Eliza Kwilecki by the Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw.

EXHIBITIONS

Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe, Le Siècle français (2009), cat. 154 (as by Watteau).

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Nicolai, Description des villes de Berlin et de Potsdam (1769), 361.

Nicolai, Beschreibung der Königlichen Residenzstädte (1779), 2: 688.

Hédouin, “Watteau” (1845), cat. 72.

Hédouin, Mosaïque (1856), cat. 73.

Mantz, L’École française (1859), 2: 347, note 1.

Goncourt, L’Art au XVIIIème siècle (1860), 56.

Cousin, Le Tombeau de Watteau (1865), 32.

Goncourt, Catalogue raisonné (1875), cat. 50.

Mollet, Watteau (1883), 62.

Hannover, Watteau (1888), 28.

Mantz, Watteau (1892), 154-56.

Rosenberg, Watteau (1896), 100.

Dilke, French Painters (1899), 88.

Seidel, Collections d’œuvres d’art françaises (1900), 39.

Fourcaud, “L’Existence de Watteau” (1901), 248-49.

Staley, Watteau (1902), 63.

Fenaille, État général des tapisseries de la manufacture des Gobelins (1903), 2: 100.

Pilon, Watteau et son école (1912), x.

Dacier, Vuaflart, and Hérold, Jean de Jullienne et les graveurs (1921-29), 1: 41; 3: cat. 227.

Réau, “Watteau” (1928), cat. 37.

Adhémar, Watteau (1950), cat. 87.

Macchia and Montagni, L’opera completa di Watteau (1968), cat. 72.

Michalkowa, “Nouvelles acquistions” (1970), cat. 66.

Ferré, Watteau (1972), cat. B 80.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1981), cat. 91a.

Roland Michel, Watteau (1984), 64, 69, 151, 266, 268.

Washington, Paris, Berlin, Watteau 1684-1721 (1984), 35.

Eidelberg, “«Dieu invenit, Watteau pinxit»”, 1997, 25-29.

Hattori, “Passeports délivrés” (2004), 24.

Michel, Le « célèbre Watteau» (2008), 121-31.

Glorieux, Watteau (2011), 68.

Vogtherr, Französische Gemälde (2011), cat. A1.

Paunet, Antoine Dieu (2018), 8, cat. 31.

Danielewicz, French Paintings from the 16th to 20th Century (2019), cat. 278.

Eidelberg, “Watteau, A Good but Difficult Friend” (2022), 47.

Paunet, “Antoine Dieu, Antoine Watteau” (2022), 110.

RELATED DRAWINGS

Antoine Dieu, Louis XIIII metant le cordon bleu à Monsieur de Bourgogne, red chalk, gray wash, 25.4 x 36.1 cm. Berlin, Kupfertsichkabinett, inv. KdZ 14837.

Watteau’s painting was based upon a drawing by Antoine Dieu that is now in Berlin. This study offered sufficient guidance for Watteau to paint the modello. Apropos of the Saisons Jullienne, another project involving both artists, Dieu supplied full compositional drawings for all four paintings in that series, and Watteau followed them closely, but not without introducing small changes. Moreover, Watteau prepared at least one additional study for one of the prominent characters in that series. Watteau may have made other such studies, as the working process was evidently fluid. A similar situation may have prevailed in the creation of Louis XIIII metant le cordon bleu a Monsieur de Bourgogne.

Differences can be observed between Dieu’s drawing and Watteau’s painted modello in Warsaw. Both are situated in the same interior where a bed, columns, and an imposing silver vase and candelabra constitute the principal elements of décor. Although both depict many characters, the drawing by Dieu provides for seventeen figures and a dog, whereas Watteau’s modello depicts only sixteen figures and no dog. Dieu’s drawing indicates the baby’s mother , Marie Anne of Bavaria, in bed in an adjoining space, whereas in Watteau’s modello, the bed curtains are only half opened, to signify more subtly the presence of the mother of the Petit Dauphin.

Most changes occurred in the figures and their reversal. In the drawing, the group of women, standing behind Louis XIV, were moved to the right. Vice versa, the group of men on the right in the drawing, with the Cardinal, were moved to the left. Watteau deleted some characters of the characters to open the composition and focus the narrative on the central action, thus giving more importance to the king, le Grand Dauphin, his wife, and the Petit Dauphin.

REMARKS

The exceptional subject and unusual nature of this composition are partially explained by Pierre Jean Mariette’s comments about the Larmessin engraving: “Watteau peignit ce tableau pour Mr. Dieu, qui avoit entrepris de peindre toutes les actions de la vie du Roy pour être exécutées en tapisserie, ce qui n'a point eu son effet.” That is to say: “Watteau painted this for M. Dieu who had embarked on representing all the events from the King’s life to have it woven in tapestry. This did not come to pass.” Mariette’s account does not explain that in June 1710, commissions were given to Dieu and other leading French painters to design tapestries commemorating the later life of Louis XIV. They were intended to complement and continue an earlier set of tapestries designed by Charles Le Brun that celebrated the early reign of Louis XIV.

In May 1710, when the Bâtiments du roi awarded the commission to Dieu, he began work by preparing compositional studies. At least one such study has survived, the one now in the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett, discussed above. The same sequence of stages, with Dieu preparing the composition and Watteau painting, can be observed in their collaboration on the Saisons Jullienne. In these collaborations, Watteau took a subsidiary role. Parmantier reversed the flow of ideas, considering the possibility that Dieu copied Watteau’s compositions, but that disregards the evidence presented here. The same situation of master and apprentice prevailed in Watteau’s work with Gillot, Audran, and other older artists. Watteau was young and still unrecognized, and such employment was undoubtedly most welcome.

In the past, few scholars paid attention to Louis XIIII metant le cordon bleu, not least because the actual picture was believed lost. It was thought to have been destroyed in an early nineteenth-century fire in Prince Friedrich Heinrich Ludwig von Preussen’s castle at Rheinfeld. However, it was indeed extant. It masqueraded under several guises, including The Birth of Jan Sobieski at Versailles, and when it passed into the collection of the Muzeum Narodowe in 1965, it was classified as an anonymous French work after Watteau. In the mid-1990s, Eidelberg chanced upon a small reproduction of the picture in the journal published by the Muzeum Narodowe (1970), where it was attributed to an anonymous French artist of the late 17th century. However, his firsthand examination confirmed that it was indeed Watteau’s autograph work. Since then, all Watteau scholars have confirmed that opinion.

As Rosenberg has noted, Dieu’s drawing and Watteau’s painted modello represent a fictive episode in the life of Louis XIV. They relate to the birth in 1682 of Louis de France, son of the Grand Dauphin and Marie-Anne of Bavaria, and grandchild to Louis XIV, future Louis XV. Dieu’s and Watteau’s compositions insist on Louis XIV’s central role in the bestowing of the Order of the Holy Spirit. In fact, it was the marquis de Seignelay, treasurer of the Order of the Holy Spirit, who brought the blue ribbon and medal to the new born once he was installed in his apartments by Charlotte de La Mothe-Houdancourt, Governess of the Royal Children.

Antoine Dieu and workshop, Presentation of the Duke of Burgundy to Louis XIV, oil on canvas, 343 × 563 cm. Versailles, château et musées, MV 2094.

Differences can be observed between Dieu’s drawing and Watteau’s modello,. And Dieu’s actual cartoon for the tapestry. First, the very subject shifted. Dieu’s cartoon does not picture the bestowing of the Order of the Holy Spirit but, rather, the presentation of the Petit Dauphin to the king by his father and governess, which is closer to what actually transpired. It is likely that after Dieu had presented the Bâtiments du roi with Watteau’s modello, the composition was discussed, debated, and modified. Thus, several characters have been added here and there, including some that Rosenberg has sought to identify but the identification of these courtiers remains problematic.

Other elements of the composition were changed. The page behind the vase no longer looks at the main action. In the cartoon, he looks down to his right. The cardinal originally at the left in the drawing, now shows his back to the viewer. Other characters have been added in the background. In the cartoon, the attendees seem more portraitistic than in Watteau’s modello.

On September 10, 1710, just four months after Dieu received his commission for this project, Watteau was issued a passport to travel to Valenciennes. The questions, then, are whether Dieu started work immediately and whether Watteau painted the modello in this brief period, before he quit Paris. More likely, as he stayed only briefly in Valenciennes, he executed the modello only after his return to Paris. This chronology essentially excludes the probability that all work on the project was compressed into the four months between May and September 1710. Indeed, the course of work was not accomplished in a short time, and final payment to Dieu was not made until 1716. Watteau would probably have been involved in the first years, closer to 1711-12. This would also correspond to the approximate time he worked with Dieu on the Saisons Jullienne. This chronology corresponds with the opinions of the few scholars who have attempted to date the work. Macchia and Montagni, as well as Roland Michel, dated the picture to 1710, Adhémar assigned the painting to 1712-15, and Paunet also centered on the period between 1711 and 1715.

Rosenberg was able to have Dieu’s cartoon unrolled , which gave him the opportunity to examine the painting closely. He believes there are indications of Watteau’s hand in the canvas’s execution.